Maps in His Majesty The King’s Reference Library

The private library of the Danish Royal Family is home to one of Denmark’s important collections of old maps. Housed at Amalienborg in the centre of Copenhagen this collection numbers approximately 11,000 items from a period of about two-and-a-half centuries, from the mid-17th to the first decade of the 20th century. Many of them printed, some manuscript, numerous rarities, others unique, nearly all of them very well preserved and of a high cartographic and aesthetic quality that conveys painstaking cartographic measurement and observation of landscapes with clarity, precision and beauty. However, despite the high quality of the collection it has remained virtually unknown territory to all but a few specialists.

The history of the map collection

The origin of the map collection is mostly unknown. While map collecting has obviously taken place throughout the century and a half during the reigns of kings Frederik V to Christian IX (1746-1906), it is not known whether the collection is older or younger than the Reference Library or contemporary with its foundation in 1746. All that is known with certainty is that important parts of the collection are older than 1794 when fire destroyed Christiansborg Palace and most of the Reference Library’s other collections then housed in the palace. This indicates that the map collection was hardly a part of the library at that time or, if so, that it must have been kept at a different location. In 1829 the map collection was mentioned for the first time and then as a separate collection with its own management housed next to the Reference Library in the apartment of King Frederik VI at Amalienborg. This was still the situation in 1840 when the Reference Library, after the ascension King Christian VIII (December 1839), moved from Amalienborg to the newly rebuilt Christiansborg Palace. Only in 1866 was the map collection formally incorporated into the Library to which it has since belonged. During the second fire at Christiansborg Palace in 1884 the map collection was saved so carefully that none of the maps seems to have suffered serious damage while many of the books were damaged more or less in connection with the rescue operation. After the fire, the Reference Library including the map collection was re-established in rooms at Amalienborg where both were kept until returning in 1922 to Christiansborg Palace, now rebuilt once again. Here the Library was to remain until 1985 when it returned once more to its present accommodation in the Christian VIII’s House at Amalienborg.

After incorporation in the Reference Library the map collection was organized and catalogued by geographer Dr Ernst Løffler who completed the task in 1872. In his report on the collection Løffler describes it as neglected but also as highly valuable with regard to both size and content. Since the early 20th century increase of the collection has been negligible. Only once has there been a significant change of its composition: when 361 maps of Norwegian military installations, primarily of the late 18th century, were taken out and donated in 1937 by King Christian X to his brother King Haakon VII of Norway to mark the 25th anniversary of both Haakon’s reign and Norwegian independence. These maps have since been given to the Norwegian National Archives. In practical terms, the map collection must therefore be considered closed. In 1967–68 the catalogue was revised and parts of the collection were repacked for the sake of better preservation.

The character of the map collection

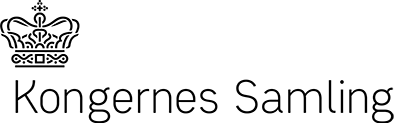

The 11,000 maps come in three different forms: Partly as a collection of about 3000 sheets, partly in around 400 atlases numbering more than 5000 maps all together, and partly as bound in the 37 volumes of the composite work known as the Atlas of Juliane Marie with a total of 2798 maps. As a whole the map collection covers the entire world in various stages of its mapping, though with an emphasis on Europe which accounts for about 80% of the entire collection. As might be expected, the collection is particularly rich in maps of the countries and territories ruled by Danish kings, i.e. Denmark proper, Norway, the dukedoms of Schleswig and Holstein, the North Atlantic possessions and the overseas colonies; close neighbours like Sweden and Germany are also extensively covered. By far the most items of the collection are geographical maps of smaller or larger sections of the world but some are also views of cities, towns and landscapes as well as material that today would not normally be seen as a map: plans of fortifications, gardens and construction projects, technical and architectural drawings. The latter in particular form a whole collection in itself containing numerous original works by the top names of 18th century Danish architecture, Nikolai Eigtved, Nicolas-Henri Jardin and C.F. Harsdorff (who have all left their mark on the Amalienborg complex). Furthermore, the map collection also comprises two smaller collections of charts and historical maps, i.e. maps that show realities past also at the time of the map’s composition.

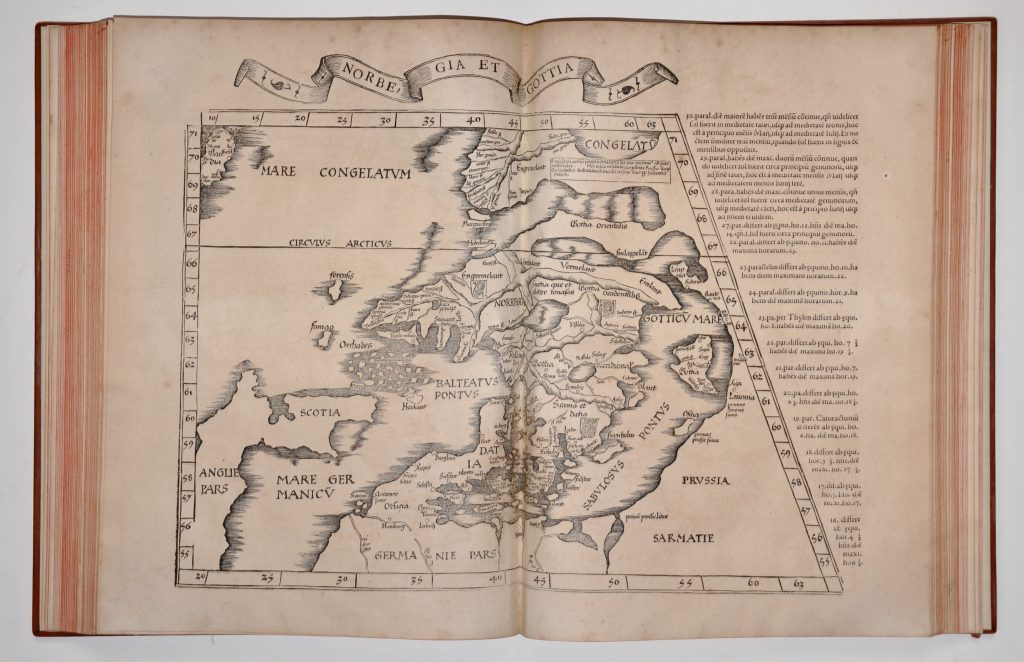

Scandinavia as mapped out in Claudii Ptolemæi Alexandrini geographicæ enarrationis libri octo

Ex. Bilibaldi Pirckeymheri tralatione, Lugduni 1535

In terms of chronology the maps cover several centuries. The Library’s oldest map – of Northern Europe – is strictly speaking not a part of the map collection but is found in an incunable, a German edition of the history by Hartmann Schedel, known as the Liber chronicarum, printed at Nuremberg in 1493. Slightly younger is an edition of 1535 of the geographical work Cosmographia by the ancient Egyptian geographer Ptolemy. Throughout the late 15th and all of the 16th centuries and thanks to the newly invented technique of printing this work came in numerous editions continuously updated in accordance with new geographical discoveries. However, apart from these and a small number of maps from the mid-17th century, the main part of the map collection dates from the period from the early 18th to the mid-19th century; the youngest maps date from the early 20th century. As mentioned, most of the maps are prints, though many coloured by hand, but the collection also comprises hundreds of manuscript maps of which a few are sketches or drafts while most are finished works.

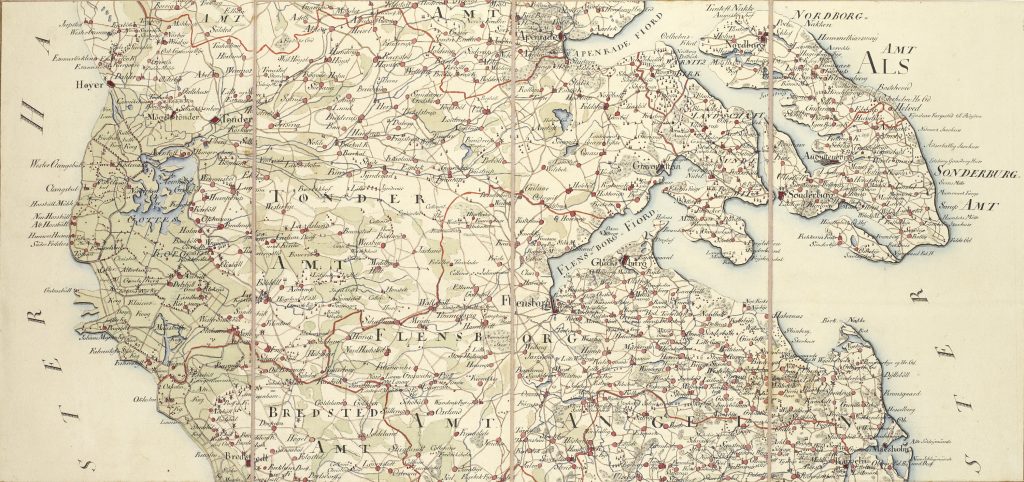

Detail of a map of the dukedom of Schleswig by du Johan Henrik Plat, drawn by Ferdinand Bauditz in 1804

Important Danish cartographers

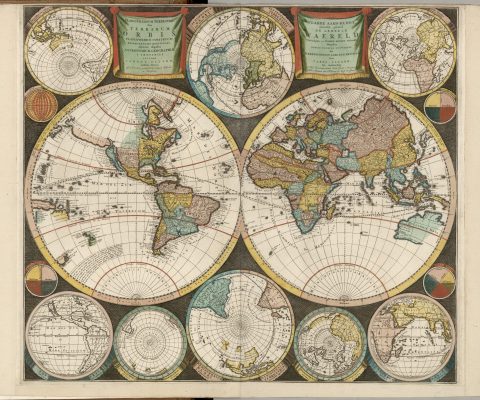

Several significant Danish cartographers are represented in the collection. Among them is Johannes Mejer (1606¬–76) who became the author of the first detailed general map of Denmark and of the dukedoms of Schleswig and Holstein (1650) as well as of a long series of maps surveying individual districts of these dukedoms. Another cartographer is Thomas Bugge (1740–1815) whose large manuscript maps (dating from 1769–71) of the Danish islands Funen, Zealand, Lolland-Falster, Møn, Bornholm and the Faroe Islands are important steps in the mapping of Danish territory. These maps must be seen in connection with the systematic trigonometric survey of the entire kingdom undertaken at about the same time by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters. In 1773 Bugge became the leader of this project and although it was to take many years to complete he can be considered a protagonist in creating the first scientifically reliable maps of Denmark. Significant contributions were also made by the army officer Johan Henrik du Plat and his colleagues whose maps of Copenhagen and environs and of the dukedom of Schleswig date from the first decade of the 19th century. In two series of 15 and 14 sheets respectively du Plat displays an unrivalled level of detail, precision and clarity. Mention should also be made of Christian Gedde whose manuscript map of Copenhagen of 1757 is a significant contribution to Danish local cartography.

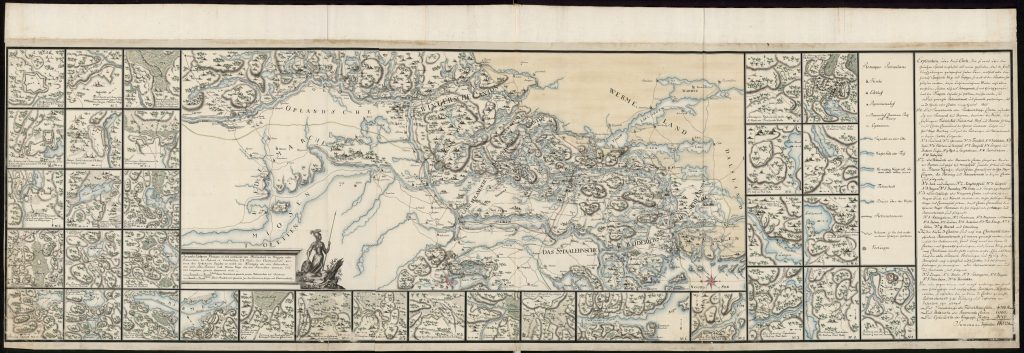

Map of the surroundings of Christiania (Oslo), drawn by Carl Alexander Stricker after Peter Iacob Wilster, 1764. Juliane Marie’s Atlas Vol. 29

The Atlas of Queen Juliane Marie

Further comments should be made on the Atlas of Juliane Marie, mentioned above, as this work constitutes a comprehensive collection in itself. In 1752 Princess Juliane Marie of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1729¬–96) married the founder of the Reference Library, King Frederik V (1723–66; king from 1746) thus becoming his second queen in which capacity she also got involved in the royal collection activities. Already as a child Frederik had received a gift, from rev. Jacob Tilli, consisting of a small collection of maps. During the King’s life-time this collection was supplemented and eventually comprised several thousand items by numerous authors and publishers and dealing with all parts of the known world. After the King’s death the individual sheets were arranged in two series: the Atlas of Frederik V and the Atlas of Juliane Marie bound identically in 55 and 37 folio volumes, respectively. For unknown reasons the two series were then separated so that the former has been kept by The Royal Library (the present-day national library of Denmark) while the latter has remained in the possession of the Royal Family and is kept in the Reference Library. In terms of content the two atlases are also alike though not identical. In both atlases the maps are arranged geographically according to country or region and so that the overall level precedes local levels. In the Atlas of Juliane Marie maps of European countries comprise 31 volumes while the remaining six cover other parts of the world as well as other kinds of images like maps of imagined countries, satirical prints, curiosities etc. Most of the maps are prints while 194 are manuscripts. The concrete details concerning the original selection and collection of the maps as well as the distribution of them between the King and the Queen are not known. Neither is it known what caused the reduction of the original number of 3311 items to the present 2798. Nevertheless, the Atlas of Juliane Marie remains the only sizeable part of the map collection whose provenance is known in more than a fragmentary manner. It is also the only part of the collection that is evidently the result of focused and systematic activity. As a whole, the Atlas of Juliane Marie can be seen as an example of the general 18th-century Enlightenment striving for systematic gathering of encyclopaedic knowledge of all parts of the world.

Collecting and applying the map collection

The other parts of the map collection appear to have been collected more randomly as occasioned by time, opportunity and need. A good deal of the maps has obviously been gifts for the king either from the author himself or from the authority, usually military, for which the author was working. This also seems to explain not only the extraordinary quality characteristic of many maps (which their authors have obviously done their utmost to achieve) but also another peculiar feature of the collection such as the uneven geographical coverage (more maps of Norway and the dukedoms than of the Danish province, for example). Unfortunately, in most cases only little or nothing is known about the background, genesis or purpose of individual maps. Usually, such details are known only in cases where they are revealed directly by the map in question or by accompanying documentation. Only in the series of maps by Thomas Bugge do we see the beginnings of an original and coherent attempt at systematic mapping of the entire country, the task undertaken by The Royal Academy of Sciences and Letters.

A collection of this size inevitably raises the question about what the many maps have been used for. However, apart from the obvious observation that they have served as a source of general geographical and topographical information about the countries ruled by the king – as well as about the outside world – the maps themselves provide only few answers. Some of them have apparently been hung on walls for orientation and decoration while others were evidently intended for use in the field and some in fact bear evidence of such use in both military and civilian connections. Still others provide documentation of borderlines or of various construction projects or current works. However, the overall impression left by the collection is one of very little use. By far the most of the maps have evidently spent most of their lives safely kept away in drawers and portfolios. Whatever the cause, this is from today’s perspective highly fortunate. As a consequence, this rich collection of rare and in many instances unique original material has been preserved for posterity in an unusually good condition. For this reason the Kings’ maps can now provide a multi-faceted and detailed impression of two centuries of development – of nature, history, politics and social life – within the vast territory that once made up the domain of Danish kings.

This text is a revised version of former reference librarian Christian Gottlieb’s introduction to the catalogue of the exhibition Mapping the Kingdom, which was held at Amalienborg Palace 14 July – 18 October 2009 in connection with The 23rd International Conference on The History of Cartography, 12-17 July, 2009.

Dansk

Dansk

English

English

Deutsch

Deutsch